For a while now, I’ve been hearing bits and pieces about how the National Ski Championships were held on Mount Hood in 1939, but I’ve never really been able to picture it in my mind.

Who competed? Where did the races take place?

And where exactly was the downhill?

Those are just a few of the questions I’ve been wondering about.

My interest was reignited the other day when my friend Jon Waldum, A Cascade Ski Club board member and Mount Hood history buff, gave me a copy of an old document he had dug up titled “The Tournament Scheme for National Ski Championships and International Team Tryouts, Mount Hood, Oregon, April 1 and 2, 1939.”

It turns out that the race was sponsored by the Cascade Ski Club — which still exists in Government Camp — and held under the auspices of the Oregon Winter Sports Association — which is no more. The Forest Service and the newly formed Mt. Hood Ski Patrol assisted with preparations and logistics, and the Wy’East Climbing Club was given the job of blasting off firework bombs to mark the start of the races.

These were the days before advanced industrial grooming, so skiers from Hood River and Bend came to help “tramp the course” for the racers. “The course will have been TRAMPED, and we mean tramped well,” wrote Tournament Director Fred McNeil, “because our contract so instructs.”

The tournament was to feature a downhill, a slalom and a combined event, and it would double as U.S. championships and a qualifier for international racers hoping to compete in the 1940 Winter Olympics in Norway. Top skiers from across North America and Europe traveled to Portland by train to be bused from Union Station up to the newly completed Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood.

Boom Years

These were boom years for skiing, particularly in the Pacific Northwest and on Mount Hood. The WPA project to build Timberline Lodge had made national news, and 10 new ski areas, all accessible by road and equipped with shelters and tows, had opened in the Northwest over the past year, staging 60 tournaments that drew big crowds.

The Golden Rose Race on Mount Hood, inaugurated in 1936, continues to this day as one of the longest continuously running races in North American history. Early winners of that race included Skibowl pioneer Boyd French, Jr., future Olympic gold medalist Gretchen Fraser and Hjalmar Hvam, the inventor of the releasable ski binding.

Lively stuff for sure — but what about the races? Where exactly did they take place?

Curiously, the 1939 Championships on Mount Hood are not mentioned in Jack Grauer’s book “Mount Hood: A Complete History.” But they are mentioned in Jean Arthur’s “Timberline and a Century of Skiing on Mount Hood.” According to Arthur, the slalom took place at Skibowl on Saturday and the downhill race on Sunday ran “from Illumination Rock at 10,000 feet to 5490 feet.”

Okay, but where exactly at 5490 feet was the finish line?

And what are we to make of the proposal in the Tournament Scheme to use portable ski tows “to get the officials and contestants out of the deep Salmon River canyon?”

Is it possible that this internationally sanctioned championship race ran from Illumination Rock down into Salmon Canyon? That would be one heck of a long left turn! We’re talking about a 4-mile race sideways, across the mountain.

Did they mean to say Zigzag Canyon? It’s pretty remote over there, but at least that run would follow the natural fall line down from Illumination Rock.

Well, Jon came to my aid once again, with some solid information from a memoir by long-time Portland skier George Henderson titled “Lonely on the Mountain.” It turns out that the finish line for the downhill race was indeed down in the Salmon River Canyon, which has been out of bounds to skiers and snowboarders for years due to avalanche danger. But the start was not up at Illumination Rock. It was at Crater Rock.

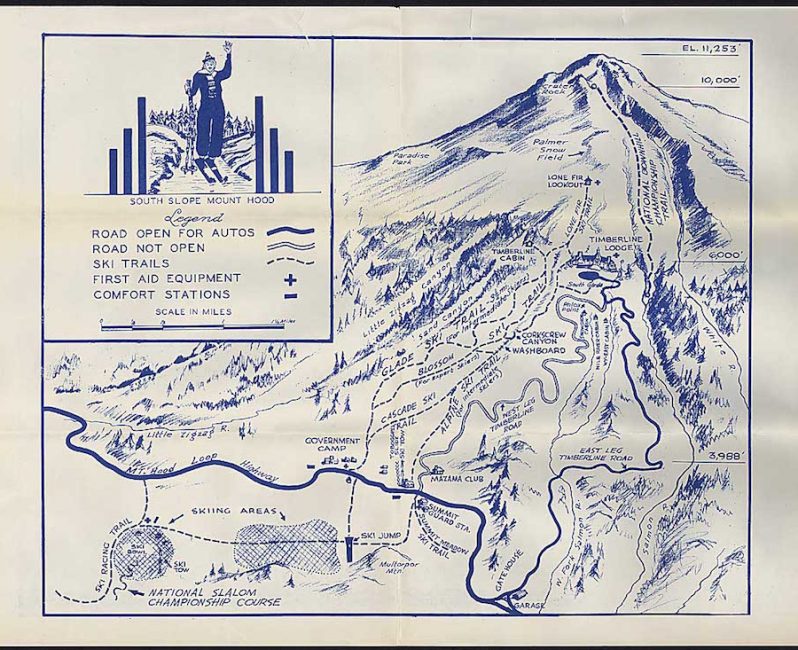

This 1939 map marked with a “National Downhill Championship Trail” above Timberline Lodge shows the straight shot once known as the Turkey Neck, from Crater Rock down to Salmon River Canyon:

“Can you imagine going flat out down this run, with the gear they had?” says Mt. Hood Museum Curator Lloyd Musser. “Most people today could not do it without stopping for a break!! On practice runs the fog was so thick they could not see the course on the upper part.”

Simply getting to the start was a three-hour hike, since the Magic Mile Chairlift was not yet completed and the Palmer lift would not be built for decades. Timberline and the Forest Service made snow cats available to the racers, but most athletes chose to hike up through the deep snow instead, to inspect the course and plan their runs.

Racers were to start in groups of similarly skilled competitors, skier-cross-style, with one-minute intervals between packs. The faster groups would go first to avoid being slowed down by having to pass slow skiers downhill.

‘Too Dangerous’

More than 100 competitors raced in the slalom Saturday and the downhill Sunday.

The slalom course started on a cornice near the top of Tom Dick and Harry Mountain with “forty pair of gates swinging racers down the undulating canyon to finish on the bowl’s level floor 900 vertical feet below.”

The men’s downhill on Sunday was set to start 500 feet above the women’s course on Mount Hood, near Crater Rock. But the great Austrian-born racer Friedl Pfeifer, who had won the slalom the day before at Ski Bowl, warned that the course was too dangerous.

After some discussion, race organizers Fred VanDyke, Fred McNeil and Boyd French, Sr. made the call to lower the men’s start by about 500 feet. Even with the lower start, the great Pfeifer failed to finish, and the combined winners ended up being Dick Durrance and Betty Woolsey.

Unfortunately, the fastest racers, including Mt. Hood ski legend Hjalmar Hvam, never did get to compete in the Winter Olympics in Norway, because the next two Winter Olympiads in 1940 and 1944 were canceled due to World War 2.

This photo of Hjalmar Hvam is blurry, but I am including it anyhow, because it gives a sense of the style of the day. Plus, I have always loved Hvam’s great quote on life and skiing: “To live and not ski is a sad life. To ski and be afraid is still worth it. But to ski and have no fear: This is to be alive!”

Thanks to Jon Waldum and Lloyd Musser for providing key details and sources for this story, and thanks to the Digital Public Library of America for the historical images.

Last modified: June 3, 2015