Russ Plaeger and Casey Gatz may not agree on many things when it comes to the forests of Mt. Hood, but they do share the perspective that 100-plus years of stopping every wildfire has created a large and complicated problem.

Plaeger is Restoration Coordinator for Bark, a Portland-based environmental group that opposes logging in Mt. Hood National Forest. Gatz is Environmental Coordinator for the Hood River Ranger District, and chief proponent of a 7,000-acre “fuel reduction” project on the north side of Mount Hood that Plaeger and Bark strenuously oppose.

The two men hold such divergent views on Polallie Cooper Spur that it seems doubtful at times that they are talking about the same project. In Gatz’s words, Polallie Cooper Spur is an initiative to protect forests and surrounding communities by carefully restoring the forest to health. In Plaeger’s estimation it is a timber sale masquerading as a fuel reduction project that would endanger the Crystal Springs Watershed and harm popular hiking and biking trails including the Dog River mountain bike trail.

They may not agree on the proposed solution, but they do agree on the cause for the problem.

“We’ve done 100 years of stopping every single fire,” says Gatz, “and when that happens you end up with a lot of small-diameter stuff that would normally get burned up in periodic fires, and it creates a real hazard.”

“A lot of these forests, especially on the east side of Mount Hood, evolved with fire, and we have excluded fire for well over a century,” adds Plaeger. “That policy is catching up with us and the forests now. Because, yes, there are a lot of fuels in the forest.”

Had it not been for a century of human intervention, the overgrown forests in this area probably would have burned naturally every 5-20 years or so. Because they have not burned, they present a risk that Gatz and the Forest Service want to lessen through thinning and prescribed burns. The basic plan, in Gatz’s words, is to “thin from below, take out the smaller stuff, and help protect the largest and healthiest trees.” In some areas, where the forest is young, the “smaller stuff” will be too small to sell profitably. In other areas, where the forest is more mature, even the small trees could be 15 inches in diameter, well worth selling as lumber. Thinning also would occur in the Crystal Springs Watershed, a drinking water source for residents of Upper Hood River Valley. The plan calls for a 55-foot buffer around the Dog River Trail, which is less than the 100-foot buffer requested by the local single-track trail group 44 Trails.

Plaeger and Bark have a problem with the plan to cut trees inside the watershed and near Dog River. They also have a larger problem with the broader strategy of restoring forests to health through logging. “Fire is one of the most exciting and fascinating phenomena that occur in our forests,” says Plaeger. “We can’t substitute logging for fire. The forests evolved with fire but they didn’t evolve with logging. It’s like with so many kinds of human interventions. Logging doesn’t do what a fire would do.”

‘Run over by the Timber Steamroller’

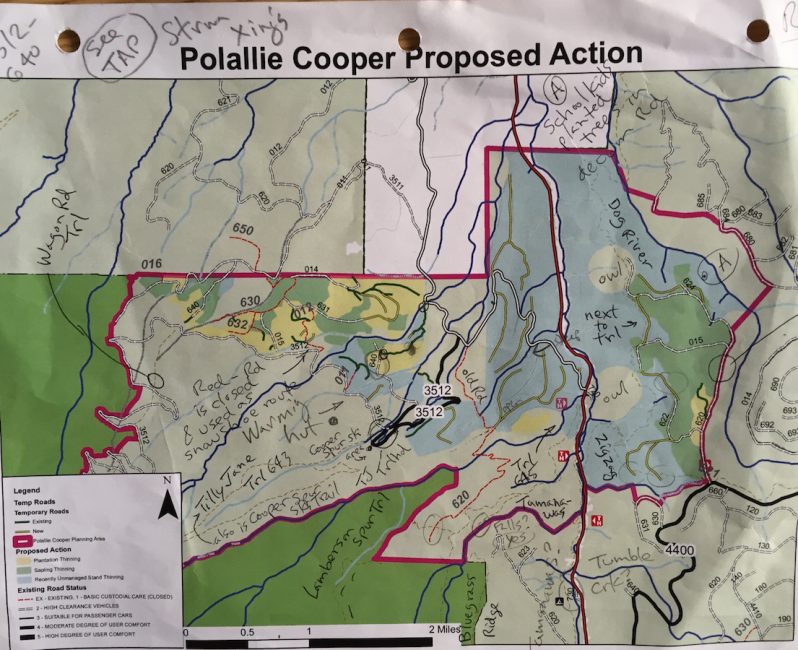

Here is a map of the proposed project, annotated in pencil by Plaeger:

As you can see, Plaeger has marked several recreational points of interest within the project area, including Tilly Jane, Cooper Spur and Tamanawas Falls. Russ, a longtime forest ranger prior to his advocacy, is informed by his own experience recreation and trails manager with the Forest Service, where he got tired of getting “run over by the timber steamroller.” In his perspective, recreation, tourism and the natural beauty of Mt. Hood National Forest are the real economic drivers, and “the priorities of Mt. Hood National Forest need to change to reflect the economics and expectations of people and the communities around them.”

The thing is, those priorities have changed, substantially. No one is suggesting clear-cutting in this forest, as was common practice in Oregon for over 100 years. A shift has definitely occurred, and as Gatz points out, the trees that are thinned out of this and all national forests will need to be sold and processed domestically because of a no-export rule to prevent over-cutting for quick profit.

Under the Polallie Cooper plan, local companies would bid on thinning and fuel reduction projects and carry them out under monitoring from a Forest Service contracting officer. After the thinning there are plans to do prescribed burns, to restore the forest to its former health and create strategically placed thinned-out areas to prevent wildfire from spreading into nearby private lands including homes.

“The forest boundary is not where the fire risk ends, or where the insects and disease end,” says Gatz. “Those things continue onto private lands. So we’re trying to provide that protection where a fire reaches a thinned area it drops down from the canopy to the ground. So we can help protect the forest as well as adjacent land-owners.”

Plaeger disputes the notion that the best solution to past wildfire suppression is more wildfire suppression: “The most effective way to reduce the fire risk to your home if you live near Cooper Spur is what you do within 100 feet of your house,” he argues. “You have a metal roof instead of a shake roof, you don’t keep your nice dry firewood pile right on the deck outside your house. You make sure you get the leaves off your deck. You don’t have your propane storage tank close to the house. Things like that. That’s what will help you in the event of a fire. Not thinning three miles away in the National Forest… Unfortunately a lot of foresters have the perspective that logging is the solution to just about everything.”

The argument could continue, and no doubt will, as the project moves closer to bidding and Bark intensifies its opposition. Spurred by Bark’s door-to-door advocacy in Portland, thousands of people have contacted the Forest Service to oppose the plan.

To learn more about this Forest Service project and how to join the debate, you can check out the documents posted by the Forest Service, or peruse Bark’s extensive critiques of the Polallie Cooper plan.

Last modified: February 24, 2016