Editor’s Note: As you may have heard, Mount Hood skier, climber, photographer and real estate pro Dale Crockatt is paralyzed from the ribs down as the result of a battle with cancer. Here is a story Dale originally wrote by typewriter in 1991, during his prime as a pioneer of high-consequence ski mountaineering on Mount Hood. It tells the story of his 11th ascent of Mt. Hood in 17 days, a day when things nearly went very, very wrong.

Mt. Hood rose proudly from a sea of clouds ending at her treeline near 6,000 feet, showing off nearly a foot of unusually dry powder snow for June 6, 1991.

Overnight, a rare continental front had moved from Montana to Oregon, leaving an exceptional day of winter snow to the few hundred skiers enjoying the new summer ski season on the Palmer chairlift at Timberline.

Driving out of the mile-thick blanket of moisture that blanketed all of Oregon, it was hard not to be excited about outwitting the state’s meteorologists as they explained to the rest of the population why their sunny forecast had turned grey. Once again, only the high Cascades escaped the clouds that covered most of the northwest United States.

I anxiously checked my backpack for all the essentials and hurried to the lift, knowing I was a little off schedule for the best conditions that day. Ideal ski conditions for spring and summer are not the winter powder storms that change to “Cascade Crud” with the first sun. Rather, week old snow, after a mild storm with light wind, transforms into miles of silky smooth “corn snow” equal to the experience of the best powder. The best corn snow conditions are late morning and early afternoon, but the best snow today — almost the longest day of the year — was at sunrise. Even though I would be 5,000 feet higher in a couple hours, it would be too late for the best snow. That did not change my mind though, because, for me, the best skiing is always up high.

In the short time it took to get ready, the dense clouds rose up the hill, fed by the warm sun and new snow, as is common for those conditions. I knew that the cooler atmosphere above would ultimately control this, and I would soon be above the fog again. I was happy to be on the mountain again while most of Oregon was trapped in the remnants of last night’s storm.

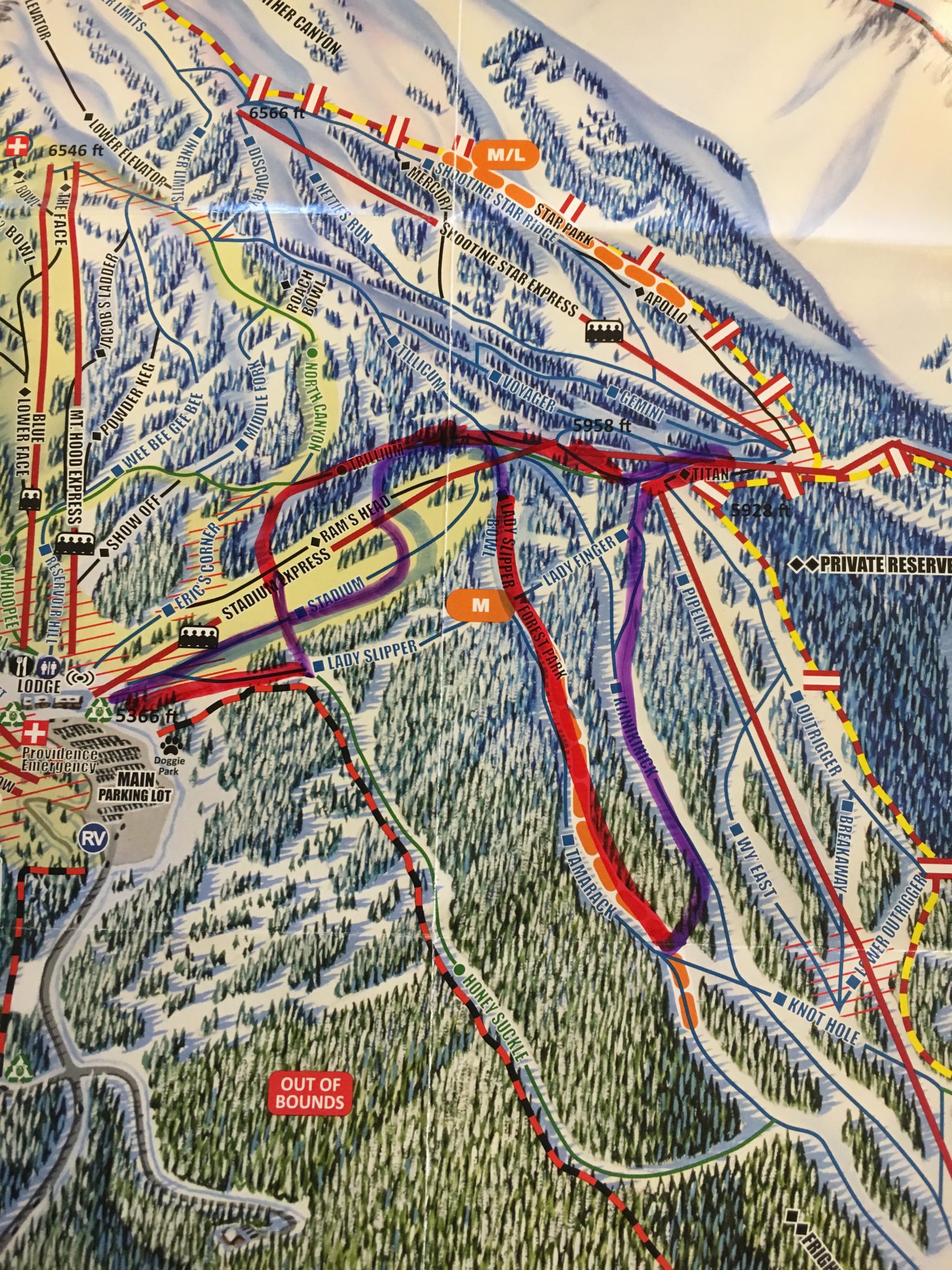

Finally, at about 8,000′ the clouds broke to again reveal the bright white peak against the cobalt sky. My adrenalin was already pumping as I anticipated this rare day. This was my eleventh ascent in seventeen days — a new record for me, as was each climb now. It was the climax of the ski mountaineering season, before crevasses and rockfall take their toll on the smooth snow slopes left by winter. I had a little doubt about my destination or route today, as I tried to read the snow and wind patterns. I was planning an eastside trip, but northeast winds and a broken trail through the foot of snow up the south side changed my mind.

At the top of the Palmer chairlift I checked in with the ski patrol as I packed my skis. There was a lot of talk about great snow and I thought about taking a run, but a 100 yard run into a 1,000′ wall of clouds below did not compare to 2,700 vertical feet of untouched powder a mile and a half away — in bright sun.

Alone on top of the clouds

I set my altimeter and started climbing, knowing that unstable new snow would make time very important today.

The snow sparkled, showing its quality, as I walked and brushed my poles easily through it. Few storms of this nature happen in winter — much less in summer — and even fewer when there is so much snow and so little wind at this elevation. It was going to be a big day!

I wished I had gotten here earlier, but was confident I could find some great skiing — even if I had to avoid the avalanche slopes. My two partners for the day had opted not to go due to the bad forecasts — so being alone I would have to play it a little safer. I would only ski the summit if time and snow permitted. I imagined a single set of turns in the snow, coming from the sky off the top to the glaciers below; boasting of the thrill of the day.

In eighteen years of climbing and hundreds of ascents in the Cascades, I could only remember a few times when the conditions were this good this high. I smiled even more looking back and seeing that the clouds had risen above the chairlift and were attempting to reach out and touch me yet before I got too far up the mountain. In one last effort the clouds caught me, but then let me climb out once and for all. Except for the three climbers 1,500′ above I was alone on top of the clouds. Voices from the ski runs below came from the clouds eerily.

I felt good, but was climbing a little slow due to the soft footing. The snow was up to my boot tops and even in the trail I could not make great time. Only a week before I had come within five minutes of my best time ten years earlier. Today it would take an hour more — two hours and ten minutes to the Hogsback at 10,500′.

I usually stop at the Hogsback to put on crampons and take a break, but today I kept going, hoping I would be able to make the last 700 feet of 45-degree slope to the summit before the snow got too bad. In the valley around Devil’s Kitchen it felt cool, and there was still hope for a summit. The soft snow did not require crampons, so I could save some time. The top was a half hour away.

Ten minutes up the Hogsback I reached the covered bergschrund that forms the major obstacle on the south side route of Mt. Hood. Late season snows left this well-covered and the route proceeded directly across the hazardous area. The steepest part of the route lies directly above this point, so I decided to test the snow.

Skimming snowballs down the steep slopes created little wheels that would build and break up into more. These were not the conditions that had allowed my last ten trips — I knew today I would not summit.

For the last two weeks Mt. Hood had been treated to sunny days and cool nights, creating ultimate climbing and ski descents. I had done several routes and descents in ten trips — including a circumnavigation at the 8-9,000′ level.

I was on a mission this year. Only a month before I used a cellular phone from high on the mountain. I was thrilled and the thought of the safety factor convinced me that I needed one for the times I was alone — or with someone.

Within two weeks I had found a shop that seemed to realize the potential of these phones in the High Cascades where there seems to be a very large reception area. On my trip around the mountain I verified reception on every glacier and ridge on Mt. Hood between 8,000 and 9,000 feet.

I knew I must have communication to continue my level of alpinism. I have been guiding over a hundred friends a year to wilderness areas untouched by most people, but eight years’ experience on a ski patrol taught me that sooner or later accidents happen to the best people. I still had all the resources available to me on the ski patrol seven years ago — with the exception of communication. Now I had communication too.

Blocks of ice and snow the size of small cars

As I kicked out a platform to put on my skis, I was confident. I was well prepared, with nearly $3,000 of high tech gear to make these situations enjoyable. It was warm — I was in a T-shirt and light pants but, as always, I put on my ski pants, coat and gloves to prepare for the steep descent. The snow was a foot deep on top of ice, and had turned to a consistency between pudding and dough.

I couldn’t help being nervous. Avalanche conditions had turned extreme in the south-facing crater with the rising heat. I would have to start a small avalanche to clear a safe skiable area down over the bergschrund. After that I would decide where to ski below. I chose not to use my self-arrest pick on my poles, and did not put on my pole straps in case I needed to abandon them. I did not expect the worst, but I was prepared for it.

I edged off the snow ridge of the Hogsback, carefully pushing a pile of snow to initiate the small avalanche that made a safe route down just east of the trail up. The slide surface was very hard — too icy to ski in those conditions — so I continued to sideslip down, facing east toward Mt. Hood Meadows.

As I went over the small roll that indicated the bergschrund I heard a familiar explosion. I kept moving, but wondered why there would be blasting avalanches at Mt. Hood Meadows — it was too late for avalanche control and too early for stump removal. NO! That was an avalanche I had heard — but where?

I didn’t see anything, so I wondered whether I had heard a sonic boom, or thunder. But there were no signs of either. I started to worry, but not seeing anything, kept moving. Instantly I saw my fate, as fifty feet of slope in front of me collapsed twenty-five feet wide. Blocks of ice and snow the size of small cars fell around me to the bottom of the crevasse 25-30′ below. The smooth slope had shattered like glass. I remember not believing how big it was, and hoping I could stay on top of it all.

My hope disappeared when I fell faster than the large roof of ice and snow. I said the world’s shortest prayer — something like “PLEASE, GOD!” — closed my eyes, content with my faith and fate, and waited for the ending. I wondered if my phone would work, or if I would even have the chance to try it. I hit the bottom on my skis, but the front of my skis, from the tips to the toes of my boots, was immediately covered with a block of snow the size of a pool table. A second block the same size landed angled on its side, falling on my back and on the tails of my skis, pinning me securely in a small hole in which I was crouched tightly. I wondered what was next — probably an avalanche triggered from the massive collapse — and if the blocks would stay put.

Blood-stained snow an inch or two in front of me on the block of snow, and on the looser snow that buried my legs to my knees, was the first sign I had that I was alive. Fortunately, for the moment anyway, I was able to realize my situation and be grateful — not dead! I actually laughed a little as I made one more wish to get out of this mess.

So this was the reason I bought a cellular phone a month ago on an impulse I couldn’t explain! I couldn’t imagine being without it with the adventures my friends and I had been taking in recent years. It all made sense to me as I put off paying bills and spent all the extra cash I had on the best phone I could buy: a Motorola Ultra Classic.

I wiggled my toes and flexed my muscles, assessing my injuries. My back had cracked a little when the second block landed on me from the rear, so I was very concerned about an injury there. All seemed well, luckily my hands were in front of me, the only parts of me I could move, except for turning my head. I dug an airspace for my head — still worried about avalanches falling into this massive cavern — and then dug in front of me and around my elbows so I could reach my phone. I made myself even smaller, checking that the blocks held themselves. I could not remove my pack, but luckily I had side pockets accessible with the pack on. The ability to reach your most important items on demand is of critical importance. There was only one thing I wanted right then.

Within a few minutes I could reach my phone. After determining reception skiing around the mountain on an earlier trip I had planned on testing it in a crevasse, but not like this! I would be able to get myself out of this eventually, as long as nothing else went wrong. Three climbers were descending above me, and I was very worried about the possibility that snow they kicked down could start even a small slide that would fill in the few holes in the blocks that were my saving.

Normally I would have dialed 911, but I knew my best chance was for a friend to come up from the lifts below, two hours away. I called Timberline Lodge and told the operator it was an emergency for the Ski Patrol or Palmer chairlift. Brad England answered and I told him where I was and what had happened. In shock, Brad responded, but we were disconnected. I pushed a single button to recall, and tried to explain to the switchboard person before I might be disconnected again. In disbelief, I heard the switchboard operator discussing it with someone else while I screamed for the Ski Patrol again.

“No helicopters!” I said. “They’ll start an avalanche.”

The ski patrol answered again, reassuring me that help was already on the way. Brad was risking his job

by leaving to help me, but I wasn’t surprised. Within minutes of this catastrophe, ambulances, helicopters and ground teams were on dispatch.

I pounded at the snow with my fists, scratched with my fingers and even bit off snow around my face as I raced time, worried mostly about the climbers above even kicking a snowball that would be enough to start a slide. My knees to my chin, my head to the snow, I could not move up enough to release my bindings. I dug at my knees and down my legs hoping to roll forward out of.my ski boots. Try after try, massaging and resting leg cramps from my effort, I fought for my life.

Decker, another ski patrol friend, calmed me on the phone.

Realizing there would not be time to remove any gear with me, I removed my pack and started to chop away at the corner of the 10″ x 12″ tunnel by my right knee. After a few contortionistic tries, I squeezed into the tunnel — so thin I had to turn my head sideways to get my nose through. I was glad to be a small person! In my socks, with phone in hand, I dragged myself to the top, several feet up.

I was still in the middle of the shattered abyss as I bridged my body from block to block, hoping not to fall through again. I went to the closest point on the downhill side of the hole where the debris filled within a few feet of the lip. There was too big a space to jump across in my socks, considering the 45-degree slope and avalanche potential if I slipped. I crawled back in and snaked across to a safer point to the east, where the crevasse was filled.

I sat on the lower edge of the crevasse, halfway down the east side of the Hogsback on a 45∞ slope in extreme slide conditions. Avalanches were happening with the least encouragement. Between me and the climbing route lay the bare ice exposed by the slide I had originally started in order to side-slip down on my skis. It would not work in socks.

Like a Shoeless Sherpa

I told Decker to cancel the rescue except for the snowcat — my back was sore and I could pay for the ride. In the meantime I decided to slide down the hill to Devil’s Kitchen. The avalanches were barely a foot deep and I chose to start a small one to avoid a larger one from above. The snow traveled slow enough down the hill, but I shot out in front of it, having only my hands for control, my phone in one. After flying 3-400′ down the hill, entirely too fast for this point of the day, I hit a bump that flew me through the air near the bottom, reminding me of my sore back. On stopping, I checked quickly to be sure I wasn’t going to be hit by the slide I started.

For some reason I decided to walk back up 200′ to the bottom of the Hogsback. I saw the other climbers coming down and wanted to warn them to go around. I told Decker on the phone I felt like a Sherpa with no shoes. On the Hogsback I met the climbers, where they gave me dry socks, sunglasses, food and encouragement. I called in “not available” for work at 6:00 that night.

Concerned, and a little amused, the climbers accompanied me to lower Crater Rock, a quarter mile away, where Brad, the patrol, met me and gave me a complete check. I refused a backboard, feeling good enough to walk. We walked another quarter mile, where a snowcat met us at Triangle Moraine at 9,600′. I rode down and celebrated life that night unlike any other. Everything was alright!

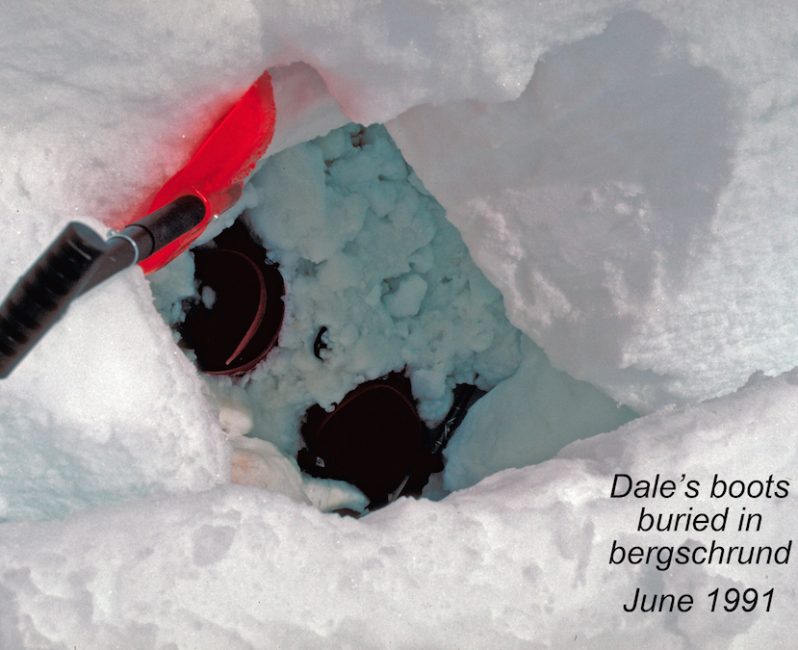

The next day I returned with my climbing partner Dale Rush to retrieve the $2,500 in gear still buried. With full rescue retrieval gear the recovery was easy, but risky, sawing blocks into pieces and digging for an hour under an overhanging ice cliff that was covered 24 hours before. I found all but one avalanche probe/self arrest ski pole, a fair sacrifice for the experience. We spent two hours down-climbing in unskiable crust with three packs and three pairs of skis — but no body — in a whiteout.

In Restrospect

In retrospect, I admit I could have avoided this accident. Two weeks of perfect ski mountaineering had left me a little overconfident. The new snow that day turned the mountain into a dangerous, but seductive, place. The time schedule I had used for the previous two weeks was no good that day, and 12″ of powder had lured me into a dangerous situation I could not recognize due to the beauty of it all.

I too, became a statistic of the trend caused by the comfort of technology in the mountains, which takes people further than they should go. For me it was just the wrong day and place. As far as climbing alone, I shudder to think of being with someone that day. There was not enough luck for two people. It might have been a girl friend who had planned on coming with me, in which case we would have been at least an hour later returning from her first summit. I would have let her go first, belaying from above, with the rope only pulling us both in. Or it might have been one of my climbing buddies who might not have been so lucky.

I don’t mind taking responsibility for myself, but I worry about taking responsibility for others.

Finally, my phone fulfilled its destiny. No longer a hypothetical situation, I lived to appreciate the premonition I had not understood. Although it did not save my life directly, it provided the best insurance available at the time. I used to say if I only needed it once in my life it was worth it. I don’t have to say that any more. It more than paid for itself in comforting me in a bad situation. I have no doubt it will do the same for anyone — and fortunately, probably, even for me again.

Dale Crockatt climbed to the summit of Mt. Hood for the first time at age 16. He served as the Director of Timberline Ski Patrol, and worked numerous search and rescue missions with the Clackamas County Sheriffs, the 304th Airborne Rescue and the Crag Rats. He also captured one of the coolest photographs of Mount Hood ever shot, showing the Hale Bopp Comet in the night sky. He began selling homes in 1997 and runs the website mounthoodhomes.com with his partner Sandi Strader.

Last modified: June 1, 2015