The night before we left on the trip we sat around the fire pit at my house, drinking beers with my wife and some friends. Sifting through Facebook out of sheer sad habit, I stumbled across a rare gem: An article entitled “Why Girls Love the Dad Bod”. It explained to the uninitiated among us, “The dad bod says ‘I go to the gym occasionally, but I also enjoy drinking heavily on the weekends and eating eight slices of pizza at a time.’” We had a good laugh and I felt vindicated. Though I am a dedicated endurance athlete, my small beer gut persists no matter how lean and strong I get.

It doesn’t take a calculator to add up the cumulative pounds of body fat on all the climbers who have summited Yosemite’s El Capitan. The answer is six. Five of them on me, and the other one divided between everyone else who has climbed in its 57-year history of ascent.

I was so unprepared for the climb I didn’t even have the perspective by which to understand how unprepared I was. I thought I was a decent rock climber, or at least a reasonably strong noob looking to take it up a level. I tried to understand how hard it was likely to be — climbing the West Face in a day — but as it turns out one cannot Youtube his way to big-wall competency.

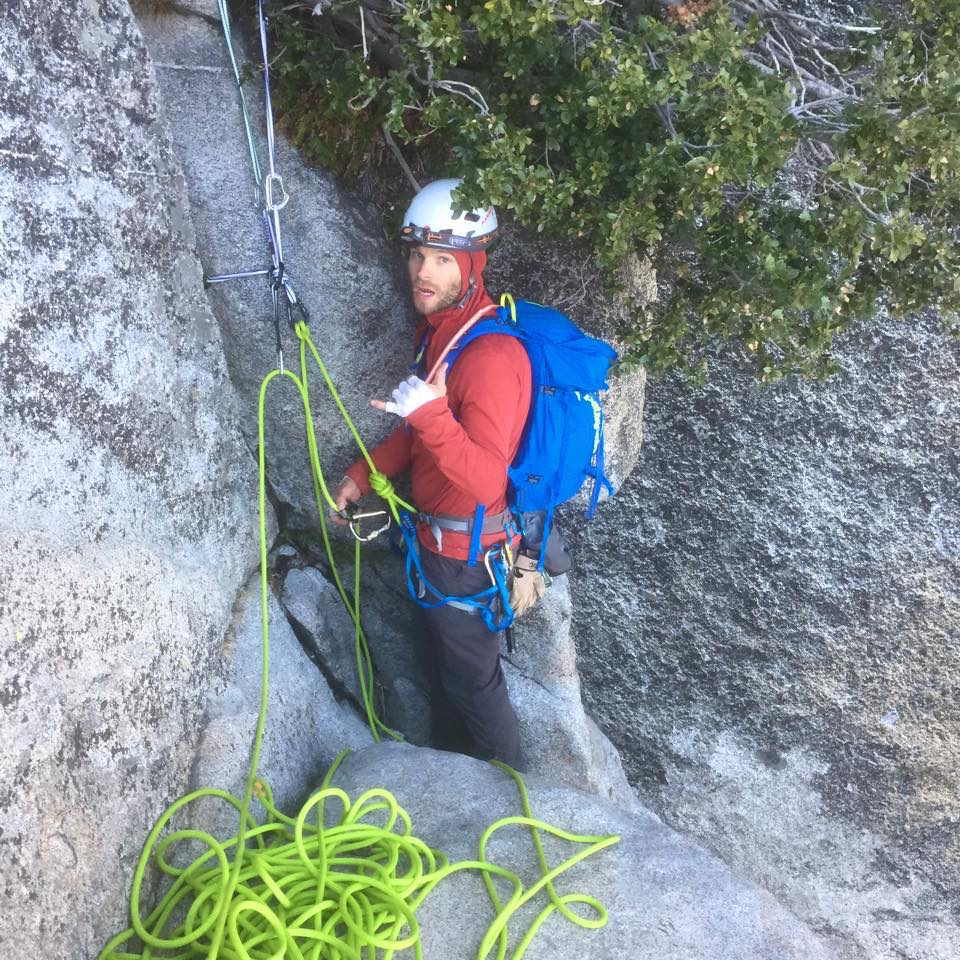

What I’ll never understand is why my friend wanted to take me up the thing. Ryan Palo would scoff at me saying so, but the only thing that separates him from some of the all-time legendary climbers is his stubborn unwillingness to live out of his van. As rock climbing is not exactly a spectator sport, people hardly pay to watch impossibly difficult ascents on pay-per-view. Many of the world’s best climbers live hand to mouth. Ryan could have had his pick from hundreds of friends and acquaintances who climb dozens of grades harder than I do. Having ticked off most of the 5.14 grade (translation: really frekkin’ hard) test-piece climbs at Smith Rock, his local crag, he doesn’t even date girls who don’t climb significantly better than me. Deciding to stick me on the other end of his rope for this monstrous climb is akin to a fighter pilot choosing the Goodyear Blimp as his wing man for a serious dogfight. But what was I going to do? Say no? Ha.

We set off from Portland at 6 am and arrived at our improvised campsite just outside of the park in time to sort some gear, drink some beer, and rack out for the night. In climbing jargon, the hike in to the base of the wall is called the “approach,” and the West Face route has the most difficult approach on El Cap. Apparently, it has killed people. The fact was not lost on me that, statistically speaking, it is almost certain that those who died on their way to the route were probably better climbers than I. And we did it in the dark. By the time we got to the wall I had so much going through my head I fumbled my figure 8 knot trying to tie myself into the rope. Ryan grabbed it from me and fixed it. I tried not to think about what went through his head.

Empathy is not a quality Ryan holds in abundance. To pass the time on the drive, he jokingly espoused his fix-all traffic enforcement and highway etiquette policy solution: roadside floggings. He argued that if only people saw the occasional citizen on the side of the road strapped down to the “Bambi basher” on the front of a highway patrol car, taking 20 lashes for driving their Cruise America rental RV 15 miles per hour under the posted speed limit in the left lane, the world would be a significantly more tolerable place. After a long discussion on the topic, he conceded that the occasional set of roadside stocks to which offenders could be affixed might suffice.

We started up the route just after 6 AM, giving us about 12 hours to top out so that we would have enough daylight to navigate the rock slabs on the other side of the summit and find the rappel anchors for the descent. Almost from the first pitch, we were in trouble.

The climbing was significantly more difficult than either of us had expected. Ryan fought hard to lead the complex route quickly but both of us were far off the pace we needed to keep. I had thought I was moving well but It turned out I was taking more than twice the 15 minutes per pitch allotted to me by our plan, and I was exhausted. We comforted ourselves by thinking that the first three were some of the most technical pitches of the climb…surely we would make better time higher up.

We didn’t. The rock was relentless and quite indifferent to our schedule. Time and time again Ryan climbed through terrifying sections on horrible gear (meaning poor or no spots in the rock to place protection that might arrest a fall). We both knew that if he came off the wall, he would do just as well having the rope coiled in his backpack as tied in to his harness. Assuming it would act as a crash pad and cushion his 600-foot fall was about as sensible as hoping it would catch him before he bounced off some chunk of granite at 80 MPH.

At one point he led out onto a blank slab where a fall would have been catastrophic.

“Mike,” he said, “do you have a Mantra?”

Confused, I grunted back something unintelligible. I did a lot of that because I was too consumed with the task at hand to put together coherent sentences.

He turned back and looked around for a decent hold. There was none.

“Because I do. ‘The rock doesn’t change if I am freaked out.’”

His point made, he artfully placed his feet on invisible waves and imperfections in the granite face and set about advancing our climb. That day Ryan did the gnarliest and bravest climbing I have ever seen. There are a lot of very strong climbers out there. El Capitan sees successful climbs every day of the season. But doing this route, leading every pitch, and getting me up it too was a tall order. It’s not that I can’t climb, but rather that I was not strong enough to contribute to the partnership in any meaningful way. I was essentially a 148 lb rump roast on the other side of the rope. I was able to haul myself up the route through a combination of free climbing and “jugging” (using mechanical ascenders to climb up a fixed rope) but I could do nothing to share the burden of leading and pace-making.

Hanging about 1100 ft above the trees below, from an anchor which inspired little confidence, I considered the role reversal in which I found myself. Ryan and I grew up in West Linn, OR and had been friends since seventh grade. In high school, I had focused my efforts on a successful wrestling career, winning some reasonable acclaim and social celebrity — at least insofar as one can do that in an oddball sport. Ryan for his part kept good grades but did so quietly so as not to interfere with a steady schedule of casual partying and teenage indifference to all things requiring motivation. We lost touch when we both left for college, where he apparently found his calling at the local rock gym. Years later we reconnected and decided to go climbing. I had stood slack-jawed that day while watching him warm up on a route much harder than anything I had ever even seen anyone climb.

It was comforting to daydream a bit, but my feet throbbed in my climbing shoes and the pain reeled back in my wandering mind.

Contrary to what one might think, climbing upwards is not nearly as scary as traversing to the side. On vertical sections of the route (assuming the rope and protection system is working as designed), falls tend to be straight down and theoretically pretty mellow. On sideways traverses climbers often swing wildly when they fall, scraping and bouncing off the rock face in the process. What’s worse is that I could not “jug” the traverse. The ascenders don’t work when you’re going sideways so with or without my own mantra, I had to follow Ryan and free climb the dicey section. Shaking and pouring sweat with my feet balanced on what seemed to be single crystals of granite no bigger than no. 2 pencil erasers, I worked my way past the crux of the pitch. I thought I had pulled it off and began to relax, leaning into the wall. The movement slightly changed the angle of my feet, and I fell.

Ryan was far above me and out of sight, but the sharp pull on the rope told him exactly what had happened. I’ve taken many falls climbing over the years but never at more than a thousand feet up. I remember it being quiet. As the rope came tight I spun which disoriented me and kept me from bracing for the impact that would come when I swung into the dihedral waiting below me and to the side. It was my right knee that hit first and stopped me cold.

I hung there for a second or two wincing in pain before the silence was broken by Ryan’s shout from above. “Get on the wall Mike,” he calmly ordered. “Get the fuck off the rope.” As I finally clawed my way up to his belay stance I understood why. He had me on what he jokingly called a “meat belay”. Unlike most of the route’s belay stations, this was a “gear anchor” and had no bolts in the wall. Instead, Ryan was tied into a hodgepodge of rusty pitons and shaky cams, all precariously placed into the same small piece of fractured stone. Balancing on a sloping rock the size of a DVD case, he had caught my fall and held me on the rope with his hands and body weight alone, not allowing any of the force to transfer to the weak anchor system. Even now I have no idea how he pulled that off. After seeing that I didn’t need to be told I couldn’t fall again.

Shaking and pouring sweat, I was too exhausted even to clip myself into the anchors. I think Ryan knew he’d pushed me about as far as I could go and finally showed some mercy.

“Well that was fucked.” He said, grinning. “That fall would have freaked me out. You OK?”

“I’m good.” I replied flatly, not able to muster a single calorie to burn for inflection.

He told me to eat something. We rested for three or four minutes, the longest break we had taken in over ten hours of climbing. I drank the last of my two liters of water.

“I’m sorry I’m so fucking slow.” I said between breaths. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me.”

“It’s the dad bod” he replied, and we both had a good laugh. Unable to retrace the traverse to get back down, we were committed now. The only way off was up and over.

A couple years ago my wife and I took a heli-ski trip to central British Columbia with Ryan and another friend from high school. We skied some very serious terrain, dropping in to multiple high-consequence pillow lines that gave us “the fear”. That term is one I borrowed from another climbing buddy and one that Ryan and I have become fond of over the years. On some level we all go to the mountains to get “the fear”. It doesn’t really mean you’re afraid per say, but rather that the intensity of the situation demands a type of concentration and dedication to purpose that’s illusive in our world of smartphones and certainty. I put Ryan on belay for the next pitch and he asked if I had gotten “the fear” yet. It was a rhetorical question.

A couple years ago my wife and I took a heli-ski trip to central British Columbia with Ryan and another friend from high school. We skied some very serious terrain, dropping in to multiple high-consequence pillow lines that gave us “the fear”. That term is one I borrowed from another climbing buddy and one that Ryan and I have become fond of over the years. On some level we all go to the mountains to get “the fear”. It doesn’t really mean you’re afraid per say, but rather that the intensity of the situation demands a type of concentration and dedication to purpose that’s illusive in our world of smartphones and certainty. I put Ryan on belay for the next pitch and he asked if I had gotten “the fear” yet. It was a rhetorical question.

As the sun dipped below the canyon rim, the evening shadow swept up the wall. I quickly pulled off my sunglasses as though I could slow the waning of daylight. We should have been done hours ago but dusk was silently indifferent to our predicament as it settled over Yosemite. With nearly a thousand feet still to climb, neither of us was ready to admit we were about to be “knighted”.

Before the evening shadow raced up the wall to engulf us, I had completely lost track of time. Now my awareness of it consumed me. We knew that even if we finished the climb that evening, we could never navigate the descent safely in the dark and instead would have to walk 13 miles on the hikers’ trail to get down. We had both been out of water for hours and we were running out of options. Not ready to give up yet, Ryan set out to lead the final hard pitch of the climb; the 240 foot section of featureless wall and crack climbing had unsettlingly long stretches with no place for protection. Slowly and painstakingly he moved up and out of sight. His grunting and swearing became more distant and eventually I heard nothing.

All there was to remind me I was not alone was the occasional tug on the neon yellow rope as it slid through my belay device. Ryan was more than 200 feet above me but I knew the climbing was brutal by the painfully small amounts of rope I paid out at each tug. I tried to imagine what it was like up there and shuddered. Finally the rope came taunt to my harness. Confused, I thought maybe I had missed him yelling “off belay,” my signal to prepare myself to follow his climb. Usually the lead climber reaches the next belay stance and calls down after he has secured himself to the next anchor. Only then does he pull up the remaining slack so that the rope comes tight to the follower. I called his name and heard nothing.

Straining my parched voice I yelled, “Ryan, ARE YOU OFF BELAYYYYYYY?”

Jumbled with my fading echo, I heard a faint but frantic “NO NO NO!”

Horrified, I realized he had run out of rope. It was now almost completely dark and I had no way to know if he was hanging in some precarious position about to take a fatal. We both yelled back and forth for what seemed like an hour. Every once in a while I could make out a word or two amidst the muddle of distant echoes.

“MORE ROPE!”

I began to climb the pitch, hoping to give him some slack. The first few meters were not terribly difficult climbing, but I had never climbed in the dark, 2,000 feet off the deck, knowing full well I was not on belay. Had I fallen, I knew I could have seriously hurt or killed us both. Given my record on the day, the thought brought chills. Slowly and deliberately, I made my way up to the first piece of gear he had placed and clipped myself into it. I felt the rope pulled up from above and a few minutes later heard a faint “JUUUUG!”, my cue to hook up my ascenders and pull myself up the rope which Ryan had managed to fix to an anchor far above.

What I saw as I moved up the rock made my stomach turn. The climbing looked vicious and there were huge sections with no protection whatsoever. I could tell he simply didn’t have enough cams (mechanical devices inserted into the rock to protect climbers if they fall) to protect the final part of the pitch. He had run out the last 50 or 60 feet with no gear at all, meaning he would have fallen more than twice that distance had he “peeled,” or had I pulled him off.

As I finally hauled myself over a massive ledge I saw Ryan calmly sitting there in the last evening shadows with his shoes off. This was to be a first for both of us: An unplanned bivouac with no overnight gear and no water. We were indeed to be “knighted” by El Capitan.

Luckily the “Thanksgiving Ledge” is enormous and allowed us plenty of room to take off our gear and get as comfortable as one can get in such a situation. Exhausted and cold, we piled some stones for a wind shelter, used our ropes for blankets, and did our best to bed down for the night. We had no cell service. I thought about my wife, who I knew was worried sick as we were hours past our scheduled check in time. I thought about my one-year-old twins asleep in their cribs at home. The thought made me colder.

By the early morning hours, a full moon had risen over the southern end of the valley. We had both shivered from the cold and convulsed with cramps through much of the night. Ryan slept a little; I did not. We crammed our swollen feet back into our climbing shoes and painfully assembled our gear, all of which I probably would have thrown off the cliff for a single glass of water. Still, it felt good to be moving up again and the short rest had brought me back from completely shattered to a more tolerable level of exhaustion. Ryan went to take a look at the next pitch as I gazed out across the valley, bathed in the light of the perfect moon. I thought about middle school.

I never really knew why, but my best friend’s mom had hated Ryan back then. We probably got busted doing something stupid with him that I have long since forgotten. Her disdain was totally baseless; we were all little assholes back then but him no more so than the rest. Whatever her reasons, she had decided that Ryan was a bad influence on us and needed to be closely monitored at all times. She went about calling all of our friends’ mothers and warning them about him. Thus was born what she called the “Parental Intelligence Agency” or “PIA”. It never really took off as she had planned, but boy she loved to talk about it. Remembering this I chuckled as I we set out to finish the last bit of technical climbing. I made my way up a wide crack in the rock, both I and it opaque in the early light. The movement felt natural and I enjoyed it immensely.

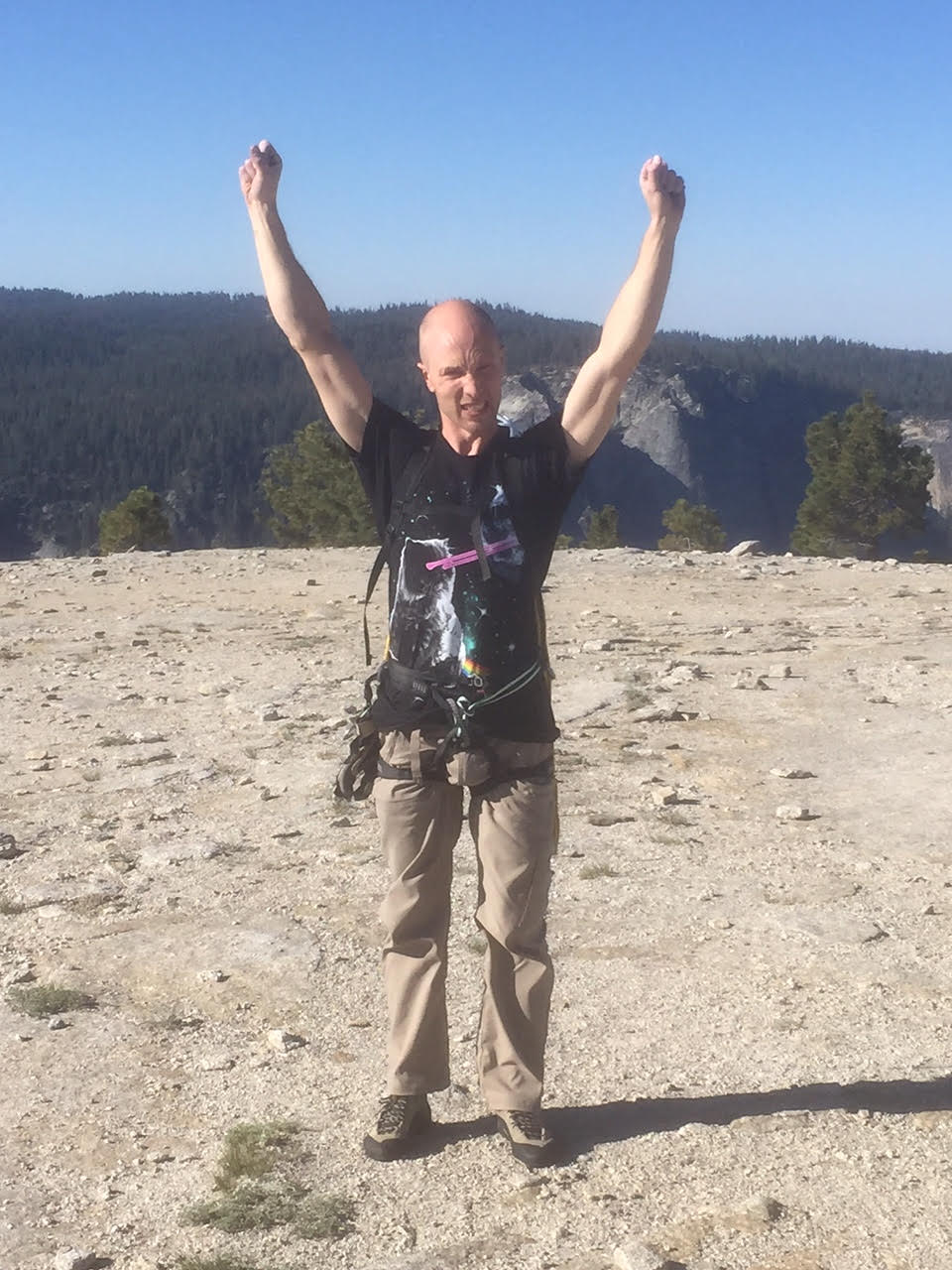

Some climbers are flooded with emotion as they top out on difficult climbs. I’m not one of them. I tend to feel something between relief and emptiness. El Capitan was no different for me. Perhaps it is the vacuum in a mind just freed of struggle and purpose. Perhaps I just had nothing left to give to emotions.

Some climbers are flooded with emotion as they top out on difficult climbs. I’m not one of them. I tend to feel something between relief and emptiness. El Capitan was no different for me. Perhaps it is the vacuum in a mind just freed of struggle and purpose. Perhaps I just had nothing left to give to emotions.

Finally unroped, I walked the last few feet of slabs below the summit. I snapped Ryan’s summit photo, one of him proudly a wearing a t-shirt with graphic of a cat shooting laser beams from its eyes (he has a thing for cats). We gathered our things and began the long descent back to the car. At one point we saw some hikers and I wondered aloud if we should ask them for a sip of water. “No,” Ryan said, “they got it up here the same way we should have.” A few minutes later, as if in a nod to his karmic mountain logic, we came across a jug of water on the side of the trail. It was left by a party who had summited that morning with a little extra. They must have thought someone else might need it. It was still cold.

We didn’t speak much on the way home. Both exhausted and daunted by the prospect of returning in such shambles to our daily grinds, we took turns at the wheel. At one point he asked me if I thought I would do something like this again. I don’t remember what I said, but I do remember thinking I probably wouldn’t. The pain of those two days was numbing and had made apparent to me the magnitude of the gap in skill and strength between where I was and where I needed to be to tackle, and master, rock climbs like that. It seemed impossible to improve that much.

Climbing El Cap was a privilege I had not earned. I should have spent years wallowing around in line at the local crag for chances to get on mediocre climbs with mediocre partners. Then maybe, if I sacrificed every moment of my free time to get strong enough and was willing to pay for gas and food, somebody without half of Ryan’s climbing resume might have begrudgingly given in to my begging him to take me up the wall. I’m not sure why Ryan took me, but I don’t spend much time thinking about things like that. I don’t presume I need to understand other people’s reasons. He’s my friend, and one I am immeasurably lucky to have.

The day after I got back (having had a little sleep and a couple beers) I was already looking at the weather forecast for Smith Rock. With so many new things to work on, I couldn’t wait to cram my feet back in to those heinous little shoes.

That night I texted Ryan, “I’m starting to forget how painful it was and remember it fondly. Almost like some sort of fun.”

He responded “Yep. That sounds about right. Climbing is great like that.”

Mike Getlin grew up skiing and hiking in the Cascades before a series of questionable life decisions landed him in Los Angeles for far too long. Having recently come to his senses and moved back to Portland with his wife and kids, he splits his time between marketing consulting (as little as possible) and climbing (as much as possible). He recently completed a solo climb up Devil’s Kitchen Headwall on Mount Hood and wrote about it for Shred Hood.

Shred Hood welcomes adventure stories and trip reports from readers and adrenaline junkies. Feel free to contact Editor Ben Jacklet with ideas and stories.

Last modified: May 20, 2015